Estimating a company's true worth isn't just about crunching numbers; it's a nuanced blend of financial analysis, market dynamics, and a keen eye for intangible value. Whether you’re selling your business, seeking investment, or navigating complex tax scenarios, mastering the various Methods of Business Valuation is crucial. It’s the difference between guessing and knowing, between leaving money on the table and securing a fair, defensible price.

This guide will demystify the art and science of business valuation, exploring the core approaches and specific techniques used by financial experts. You’ll learn when to use each method, understand the data required, and discover the hidden factors that can significantly swing a company's value.

At a Glance: Key Takeaways

- Valuation is Situational: The purpose of your valuation (e.g., selling, tax, investment) dictates the most appropriate methods.

- Three Core Approaches: Asset-based, market-based, and income-based methods form the foundation. Often, a combination yields the most accurate picture.

- Beyond Tangibles: Intangible assets like brand reputation, strong management, and strategic location can significantly boost a company’s worth.

- Small Business Nuance: Methods like Seller's Discretionary Earnings (SDE) are tailored for owner-operated businesses.

- Challenges Abound: Data limitations, market volatility, and reliance on future assumptions make valuation complex.

- Expertise Matters: While DIY has its place, professional valuators offer specialized knowledge, uncover hidden value, and add credibility.

Why Pinpoint Your Company's Worth? The Critical Role of Valuation

Imagine trying to sell your house without knowing its market value, or negotiating a salary without understanding industry benchmarks. Sounds risky, right? The same principle applies exponentially to businesses. Business valuation is an objective process that determines a company’s economic worth, providing confidence and clarity in high-stakes financial decisions.

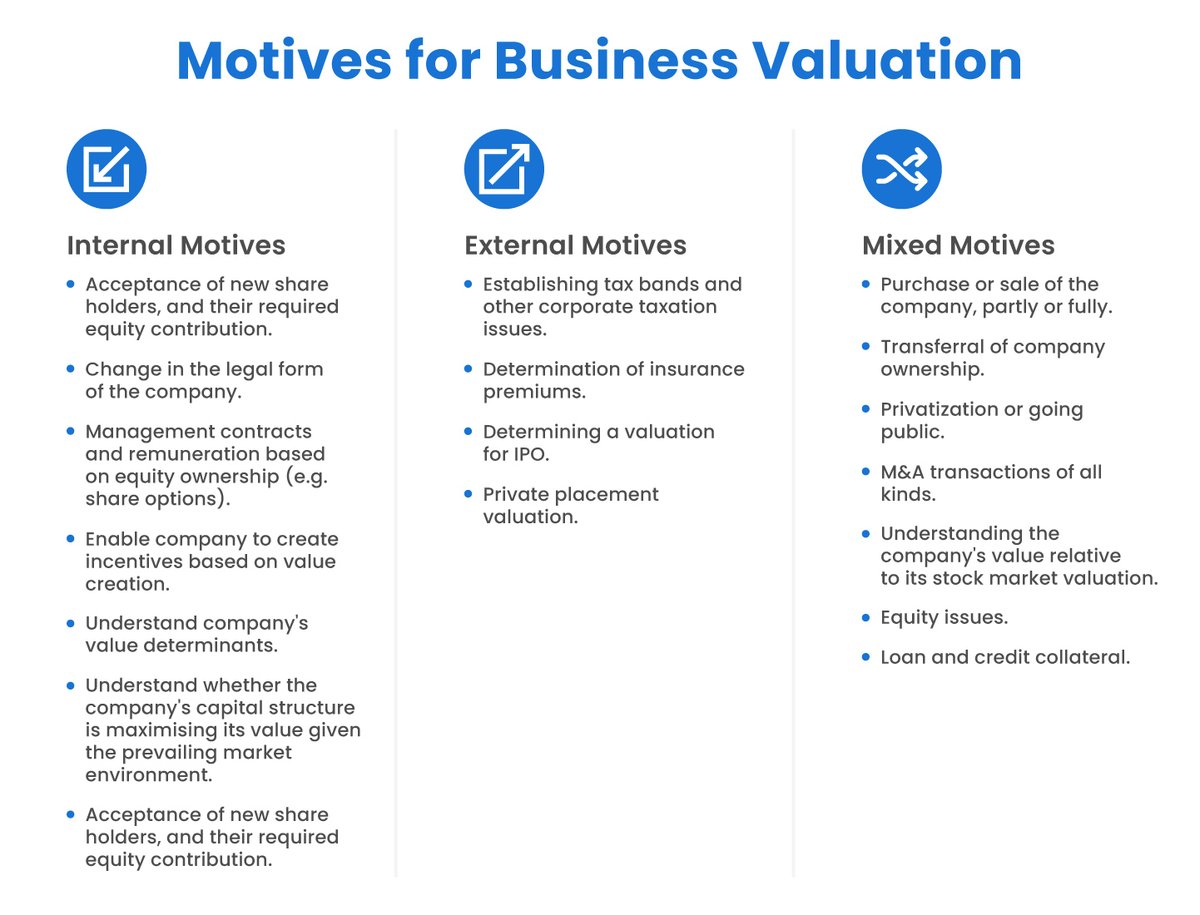

You'll find yourself needing a valuation in a surprising array of scenarios:

- Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A): For buyers, it’s about determining a fair purchase price; for sellers, it's about maximizing value.

- Tax Compliance: From estate tax planning to 409A valuations for equity compensation, accurate valuations are non-negotiable.

- Financial Reporting: Meeting regulatory requirements often demands up-to-date valuations of assets and business units.

- Strategic Planning: Understanding your company's value helps in setting growth targets, identifying key value drivers, and making informed investment decisions.

- Securing Loans or Raising Capital: Lenders and investors need to assess risk and potential returns, making a credible valuation essential.

- Ownership Changes & Legal Disputes: Whether it's gifting shares, divorce proceedings, or shareholder disagreements, a clear valuation ensures equitable outcomes.

- Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOPs): Establishing a fair price for employee shares.

- Insurance Needs: Determining adequate coverage for your business assets and operations.

Here’s the golden rule: the purpose of your valuation dictates the approach. Selling a business, for instance, might involve highlighting growth narratives and comparable sales to justify a premium. In contrast, a 409A valuation for stock options demands a highly objective, defensible Fair Market Value that stands up to IRS scrutiny. No two businesses are alike, and therefore, no single valuation method fits every scenario perfectly.

The Three Pillars of Business Valuation: A Comprehensive Framework

At its core, business valuation methodologies generally fall into three broad categories:

- Asset-Based Approach: Focuses on what a company owns.

- Market-Based Approach: Compares the company to similar businesses.

- Income-Based Approach: Projects a company's future earning potential.

While each approach offers a distinct lens, a seasoned valuator often employs a combination of methods. This multi-faceted perspective helps to cross-check results, balance the limitations of individual techniques, and ultimately provide a more robust and credible estimate of value. Think of it like a chef using multiple ingredients to create a balanced, flavorful dish—each method contributes to the overall "taste" of the valuation.

Pillar 1: The Asset-Based Approach – Valuing What You Own

This approach values a company primarily by assessing the cost of its net assets. It's particularly useful for businesses that are asset-heavy (e.g., manufacturing, real estate), early-stage companies without substantial revenue or profit history, or those facing potential liquidation.

Book Value

The simplest form of asset valuation, Book Value calculates a company's worth by subtracting its total liabilities from its total assets, as recorded on the balance sheet. It's a snapshot based on historical cost, not necessarily current market worth.

- Formula:

Value = Value of Total Assets on Books – Value of Total Liabilities on Books - Example: A company with $12 million in assets and $5 million in liabilities has a book value of $7 million.

Net Asset Value (NAV) Method

This method takes Book Value a step further by adjusting the assets and liabilities to their current fair market value. It provides a more realistic picture of what a company's net assets are truly worth today.

- Formula:

Value = Fair Value Total Assets – Fair Value Total Liabilities

Liquidation Value

A "worst-case scenario" valuation, the Liquidation Value estimates the cash that would be realized if a company's assets were sold off immediately and all liabilities were paid in full. Assets are typically valued at a significant discount due to the urgency of the sale. This is relevant for distressed businesses or bankruptcy proceedings.

- Formula:

Value = Sum of Value of Assets at Discount – Liabilities - Example: A business with assets that could be liquidated for $8 million, and $5 million in liabilities, would have a liquidation value of $3 million.

Cost to Replace Method

This method estimates the current cost of acquiring a substitute asset with similar functionality and utility. It doesn't aim to recreate the exact original asset but rather an equivalent one. Think of replacing an old piece of machinery with a new, more efficient model that performs the same job.

Reproduction Cost Method

Unlike the Cost to Replace method, Reproduction Cost estimates the expense of recreating an exact replica of an asset. This includes all direct and indirect costs associated with building or manufacturing the asset precisely as it exists. It’s often used for unique or historical assets where exact replication is the goal.

Pillar 2: The Market-Based Approach – What the Market Says You're Worth

The Market-Based Approach values a company by comparing it to similar businesses that have recently been sold or publicly traded. It's most effective for companies with established revenue, a clear financial history, and readily available comparable market data. This approach is inherently forward-looking, reflecting current market sentiment.

Market Capitalization

Applicable only to publicly traded companies, Market Capitalization is simply the total value of all a company's outstanding shares.

- Formula:

Market Capitalization = Share Price × Total Number of Shares Outstanding - Example: If Microsoft Inc. has 7.43 billion shares outstanding and its stock trades at $515.74 per share, its market capitalization would be approximately $3.83 trillion.

Times Revenue Method

This straightforward method applies an industry-dependent multiplier to a company's annual revenue stream. The multiplier varies significantly by industry, reflecting typical profit margins, growth rates, and risk profiles.

- Example: A software firm with $10 million in annual revenue, operating in an industry where businesses typically sell for 3x revenue, would have an estimated value of $30 million.

Earnings Multiplier

Similar to the Times Revenue method, the Earnings Multiplier applies a multiple to a company’s annual earnings (often EBITDA – Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization), adjusted for factors like current interest rates, growth prospects, and risk.

- Example: A company consistently earning $5 million annually, valued at 8x earnings, would be estimated at $40 million.

Guideline Public Company (GPC) Method

This technique analyzes valuation multiples (e.g., price-to-earnings (P/E), price-to-sales (P/S), Enterprise Value to EBITDA (EV/EBITDA)) from publicly traded companies that are similar in industry, size, and operations to the target company.

- Formula:

Value = Comparable Company Multiple × Subject Company Metric (e.g., EBITDA, Sales)

Guideline Transaction Method

Instead of public companies, this method derives value from multiples observed in recent merger and acquisition (M&A) transactions involving businesses comparable to the subject company. It focuses on actual sale prices rather than public market trading prices.

- Formula:

Value = Comparable Transaction Multiple × Subject Company Metric

Subject Company Transaction Method (Precedent Transaction Method)

This method specifically looks at a company's own recent financing activities—such as a recent equity sale or capital raise—to determine a per-share value, which is then extrapolated to the entire company.

- Formula:

Value = Price per Share (from recent transaction by the company) × Total Shares Outstanding

Pillar 3: The Income-Based Approach – Your Future Earning Potential

The Income-Based Approach posits that a business is worth the sum of its future economic benefits, discounted back to their present value. It's ideal for companies with stable, predictable earnings, a clear operational history, and reliable financial forecasts. This is often considered the most theoretically sound approach, as it directly reflects a buyer's primary motivation: future cash generation.

Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) Analysis

DCF is arguably the most common and robust income-based method. It involves projecting a company's free cash flows into the future (typically 5-10 years), estimating a terminal value for all cash flows beyond that projection period, and then discounting all these future cash flows back to the present using a discount rate. This rate reflects the business's risk profile and the time value of money, often ranging from 8-12% for stable businesses.

- Formula:

Value = (CF1 ÷ (1 + r)^1) + (CF2 ÷ (1 + r)^2) + … + (CFn ÷ (1 + r)^n) + Terminal Value ÷ (1 + r)^n - Where

CF= projected free cash flow for a period,r= discount rate,n= number of periods. - Example: A business expected to generate free cash flow of $2 million annually for five years, with a suitable discount rate of 10%, might be valued at approximately $7.6 million for the explicit forecast period alone (before considering terminal value).

Special Spotlight: Seller’s Discretionary Earnings (SDE) for Small Businesses

When valuing small, owner-operated businesses, traditional income measures like EBITDA can be misleading because the owner’s compensation, perks, and non-essential expenses are often intertwined with the business's profitability. This is where Seller’s Discretionary Earnings (SDE) comes in.

SDE is a crucial metric that adjusts a business’s reported net profit to reflect the total financial benefit an owner receives from the business, assuming a single owner-operator. It adds back:

- The owner's salary and personal benefits.

- Non-recurring or non-essential expenses (e.g., one-time legal fees, owner's personal vehicle, excessive travel).

- Interest, depreciation, and amortization.

The resulting SDE provides a clear picture of the true profitability available to a new owner, free from the previous owner's specific discretionary choices. Once SDE is calculated, it is multiplied by an industry-specific multiple, which typically ranges from 1 to 4 for most small businesses. However, for high-growth sectors like tech or SaaS, these multiples can easily reach 3 to 5 times profit or even higher. - Example: A local restaurant with an SDE of $250,000, operating in an industry with an average SDE multiple of 2.5, would have an estimated value of $625,000.

Beyond the Balance Sheet: The Intangible Influencers of Value

While financial statements provide a quantitative foundation, a business's true worth is often profoundly shaped by factors that don’t show up directly on the balance sheet. These "intangibles" can justify a significant premium and differentiate an average business from a truly exceptional one.

- Brand Reputation and Strategic Value: A strong, well-regarded brand signals trust, quality, and customer loyalty. It often translates into pricing power, easier customer acquisition, and sustained revenue. Buyers will pay more for a brand with inherent market pull and positive public perception.

- Geographical Location: For many businesses (retail, hospitality, manufacturing, services), a prime location can be a massive asset. Operating in a high-demand area, a strategic distribution hub, or a region with access to specialized talent significantly increases attractiveness and potential revenue.

- Valuation Circumstances: The "why" behind the sale matters. A motivated seller under pressure (e.g., forced sale due to illness) might accept a lower price than one strategically exiting at the peak of their business's performance. Favorable market conditions and negotiation power can lead to better outcomes.

- Business Age: Newer companies often offer explosive growth potential, attracting venture capitalists. Established businesses, however, provide stability, proven processes, customer bases, and reduced risk—factors that appeal to different types of buyers and can command a premium for reliability.

- Market Conditions and Risk Factors: The broader economic environment plays a huge role. A booming economy with high consumer confidence might lead to higher valuations across the board. Conversely, a volatile market, intense competition, regulatory changes, or susceptibility to economic downturns can depress valuations.

- Synergies: In the context of M&A, synergy refers to the potential for cost savings (e.g., combining operations, eliminating redundancies) or revenue growth (e.g., cross-selling, expanding market reach) that results from combining two businesses. A buyer will often pay a control premium for a target company if they foresee significant synergistic value.

- Quality of Management: A strong, experienced, and stable management team is invaluable. It inspires confidence in a company's future performance, operational efficiency, and ability to adapt to challenges. Buyers are often willing to pay more for a business with proven leadership that can ensure a smooth transition and continued success.

- Barriers to Entry: What makes your business difficult for competitors to replicate? Proprietary technology, exclusive long-term contracts, patents, trade secrets, high capital requirements, or complex regulatory hurdles create defensible competitive advantages that significantly enhance value.

- Control Premium: When a buyer acquires a controlling stake (50%+ ownership) in a company, they gain the power to make all strategic and operational decisions. This ability to fully direct the business often comes with a "control premium"—an additional amount paid over the per-share value of a minority stake.

Navigating the Treacherous Waters: Common Business Valuation Challenges

While methodologies provide structure, the real world of valuation is rarely straightforward. Several inherent complexities can make arriving at an accurate valuation a significant challenge.

Data Limitations

One of the most frequent hurdles is inconsistent, incomplete, or simply unavailable financial records. Early-stage companies might lack a multi-year financial history, while small businesses may have poorly kept books. Additionally, finding truly comparable market data for unique businesses can be difficult, leading to reliance on imperfect proxies.

Untangling Intangible Assets and Goodwill

Traditional accounting often struggles to capture the true economic value of intangible assets like brand reputation, customer lists, proprietary software, or unique processes. Goodwill, representing the value paid for a company beyond its tangible assets, is particularly nebulous. Valuing these elements requires specialized expertise and goes beyond simple balance sheet analysis.

Market Volatility

Economic shifts, changes in interest rates, geopolitical events, and even industry-specific trends can impact a company's current value and its future earnings potential. Over-reliance on historical data without considering forward-looking market dynamics is a significant risk. Valuations conducted during periods of market uncertainty may need frequent reassessment.

The Peril of Assumptions

The income-based approaches, especially DCF, heavily rely on projections of future performance (revenue growth, cost structures, capital expenditures). These are inherently assumptions, and even slight inaccuracies in these forecasts can drastically alter the final valuation. The further out the projections go, the more uncertain they become, requiring careful justification and sensitivity analysis.

DIY vs. Expert: When to Call in a Professional

You might be tempted to try a DIY valuation, especially for a small business. After all, you know your business best, and it could save you money. Here’s a quick comparison:

DIY Valuation

- Pros: Cost savings, deep familiarity with your own business, quick initial estimate.

- Cons:

- Inaccuracy: Easy to overlook subtle financial nuances, misinterpret market data, or apply incorrect multipliers.

- Undervaluation/Overvaluation: You might either sell yourself short or price your business out of the market.

- Missing Intangibles: Difficulty in objectively assessing and quantifying intangible assets like brand or management quality.

- Lack of Objectivity: Emotional attachment can cloud judgment.

- No Credibility: Lacks the independent, professional backing needed for negotiations, tax authorities, or legal proceedings.

Professional Expert Valuation

- Pros:

- Specialized Knowledge: Valuators are trained in diverse methodologies and industry-specific nuances.

- Objectivity: Provides an unbiased assessment, free from emotional bias.

- Hidden Value Assessment: Can identify and quantify intangible assets or synergies you might miss.

- Credibility & Defensibility: A professional report carries significant weight with buyers, lenders, investors, and regulatory bodies.

- Negotiation Power: Equips you with a strong, defensible position in any negotiation.

- Strategic Insights: Experts can often highlight areas for value creation or potential risks.

- Cons: Cost (though often an investment that pays for itself).

While a DIY estimate can be a useful starting point for internal planning, for any high-stakes situation—selling, securing funding, or tax compliance—engaging a professional valuation expert is almost always a wise investment. They bring not just numerical expertise, but also the art of interpreting market signals and future potential.

Getting Started: Documents You'll Need for a Valuation

To conduct a thorough and accurate business valuation, your chosen expert will require comprehensive documentation. Preparing these in advance can significantly streamline the process. Expect to provide:

- Financial Statements:

- Profit & Loss (Income) Statements for the past 3-5 years.

- Balance Sheets for the past 3-5 years.

- Cash Flow Statements for the past 3-5 years.

- Tax Returns: Federal and state income tax returns for the past 3-5 years.

- Detailed Asset & Liability Schedules:

- Accounts Receivable Aging Report.

- Accounts Payable Aging Report.

- Fixed Asset Schedule (listing equipment, property, with acquisition dates and costs).

- Inventory Valuation Reports.

- Loan agreements and debt schedules.

- Legal & Corporate Documents:

- Articles of Incorporation/Organization.

- Bylaws/Operating Agreement.

- Shareholder/Partnership Agreements.

- Key contracts (customer, vendor, lease agreements).

- Business Overview:

- Company history and organizational chart.

- Business plan, mission, and vision statements.

- Marketing materials, product/service descriptions.

- Resumes of key management personnel.

- Financial Projections:

- Detailed financial forecasts (revenue, expenses, cash flow) for the next 3-5 years.

- Assumptions underlying these projections.

- Industry & Market Data (if available):

- Market research reports.

- Competitive analysis.

Your Next Steps: Making Sense of Your Business's True Worth

Understanding the various methods of business valuation is more than just academic; it’s about empowerment. It equips you to speak intelligently with potential buyers, investors, or lenders, and to make strategic decisions that genuinely reflect your company's potential.

Remember, valuation is not a precise science, but an informed estimate based on a blend of art, science, and experience. By grasping the core principles—asset, market, and income approaches, the critical role of SDE for small businesses, and the powerful influence of intangibles—you're well on your way to truly understanding your company's worth. Whether you decide to tackle a preliminary valuation yourself or engage a seasoned professional, this knowledge will serve as your compass, guiding you toward accurate, credible, and ultimately, more successful outcomes.

Note on Placeholders:

The provided "CLUSTER LINKS" section in the prompt was empty. Per the instructions, "Use ONLY the placeholders provided in CLUSTER LINKS; do NOT invent new slugs or change any slug," I have omitted placeholder links from this article to avoid generating incorrect or unmappable slugs.